Coral Reef Conservation Heroes Part 3 of 4: Dr. Alan White

November 4, 2020Dr. Alan T. White currently serves as the Chief of Party for the USAID Sustainable Ecosystems Advanced Project in Indonesia. Alan has decades of experience with coastal management, implementation, and research, with fieldwork in the Philippines and other parts of Southeast Asia, including substantial work with the Coral Triangle Atlas, an online GIS database of the region established in 2010 as part of the Coral Triangle Initiative.

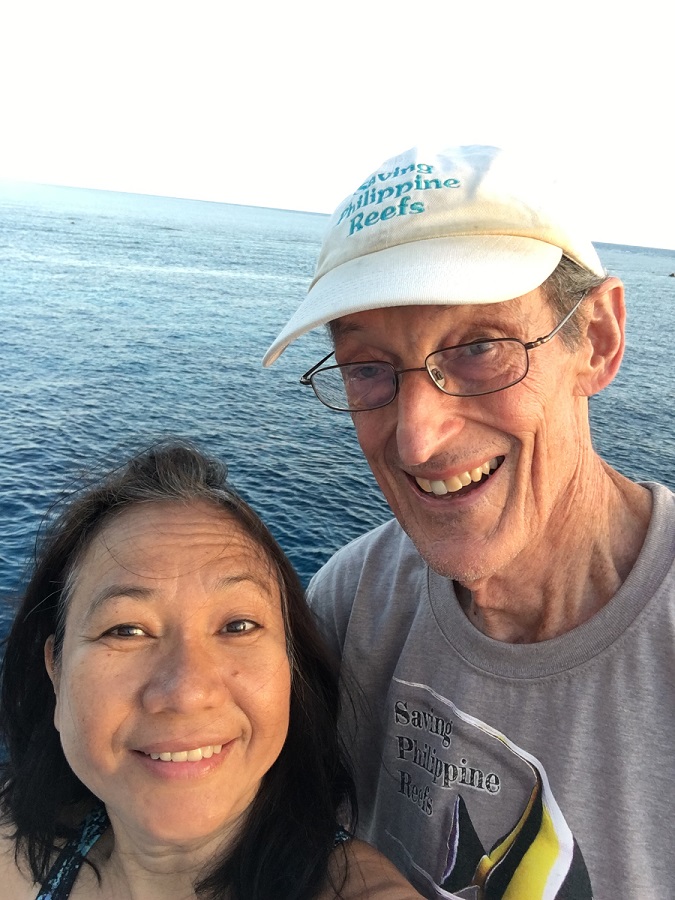

Alan and Vangie White on a recent Saving Philippine Reefs expedition in Cebu Island. (Photo by Alan White, 2019)

How did you first get interested in coral reefs?

When I graduated from university, I joined the Peace Corps and was assigned in the Galapagos Islands. Though Galapagos is not known for its coral reefs, I became interested in marine conservation due to the many marine life issues occurring in the Galapagos in the 1970’s.

Then in the late 1970’s, I worked with a task force in the Philippines to scope out marine protected areas (MPAs) for the country. It was then I realized the urgent need to protect, conserve, and manage coral reefs for all of their ecological, economic, and social values. I proceeded to do my dissertation research in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia on the development and management of coral reef MPAs in the early 1980’s, which opened all the opportunities and challenges regarding coral reef conservation.

Alan on boat dock of Charles Darwin Research Station, Academy Bay, Santa Cruz Island, Galapagos where afternoon breaks from writing the Galapagos Guide included a swim in the bay. (Photo by Alan White, 1972)

What is your role right now and how long have you been in this field?

I have worked in the field of marine conservation for over 40 years. My role now, and in recent years, is to manage donor projects in Southeast Asian countries that focus on integrated coastal resource management, MPAs, coral reef conservation, fisheries management, capacity building, and related activities that support and promote improved marine stewardship of coastal and marine resources. I currently manage the USAID-supported Sustainable Ecosystems Advanced (SEA) Project in Indonesia (2016-2021) that among other objectives is adding more than 1 million hectares (3861 square miles) of new and well-designed MPAs in eastern Indonesia.

What’s the biggest challenge you face today in your work?

While there are many challenges in the field of marine conservation and tropical coastal resource management, I suppose the largest one overall is the effective uptake by responsible government bodies to integrate the needs of coral reef protection and related conservation objectives into their plans, budgets, and legal mandates so that long term programs are well designed and sustained.

In today’s world most developing country governments, where most coral reefs exist, are concerned with keeping their constituencies on favorable terms through economic well-being and food security. These priorities don’t easily connect with strict marine conservation and protection measures. Thus, our challenge is to present the work we do in terms that support economic development so that policy makers can grasp the value. And, in the Coral Triangle countries that include Philippines and Indonesia, the governments have fully understood the value of coral reef conservation and management for the value of biological diversity, fisheries, and food security through the implementation of the Coral Triangle Initiative. But of course, such an initiative does not begin to solve all the problems of coral reef conservation but is a good first step!

Saving Philippine Reefs (SPR) survey team in Bohol, Philippines. The SPR surveys started in 1992 and have been conducted every year since covering more than 50 large and small MPAs and accumulating a dataset on the status and trends of reefs in all survey sites for which analysis and publication continues. (Photo by Alan White, 2007)

What do you see as the potential impact the Allen Coral Atlas can make for the world’s coral reefs?

The Allen Coral Atlas will help raise awareness about coral reef values and ideally make credible spatial data more readily available for planning MPAs and similar marine conservation interventions. Having an accurate source of information on reef locations and reef quality is an essential first step in planning effective protection measures and locations.

How do you think the Atlas can help you build capacity to deal with spatial data, for example, in Indonesia?

The Allen Coral Atlas can potentially provide a sound source of baseline spatial information on the major reef systems in Indonesia when fully online. But because Indonesia is a very large country with almost 18% of the world’s coral reef area within it area of jurisdiction, the Atlas will be most effective to focus initially on specific areas for which marine protection is being planned and implemented, so that the data is focused and of a scale and level of detail that will assist in the planning efforts. Also, the audience for the Atlas data will be the government agencies responsible for marine spatial planning in the country and the many NGOs that operate in Indonesia to support improved marine resource management. National universities doing marine related research will also benefit from the Atlas.

Alan counting fish over the large expanses of branching Acropora coral in Tubbataha south reef that has fully recovered from blast fishing in the 1980s and the severe bleaching in 1998. (Photo by Vangie White, 2018)

You have experience with another atlas – the Coral Triangle Atlas. How has the tech changed since the creation of that atlas? What hasn’t changed?

The purpose of the Coral Triangle Atlas (CT Atlas) is to serve as a tool for the six Coral Triangle countries to track their progress in the implementation of marine protection and management activities that focus on managed seascapes, fisheries, MPAs, adaptation to climate change, and threatened species. While the information technology is changing and becoming more efficient, the bottom line is the human capacity to use the technology wisely. Thus, while the computer and information technology that goes into the CT Atlas is being upgraded to make it simpler and easier to use and to provide a more efficient source on data, the need to build human capacity and understanding to use it does not change and is a variable that is not always consistent or predictable and still needs much support.

How have you seen communities benefit from restored coral reefs?

Many communities in Southeast Asia that have set up effective reef protection programs in their areas of jurisdiction see multiple benefits from improved or stable reef fisheries, improved food security, and income from localized tourism opportunities. They also have realized the benefits related to their social well-being by feeling that they are the stewards of their reef resources.

Most “restored” reefs that I have seen are through simply stopping destructive activities, limiting overfishing and preventing undue impacts from land based pollution and shoreline development. When communities take these actions, they see these returns within a few years and they are usually converted to become reef stewards because they have witnessed the progression from degradation to improvements and tangible benefits.

Massive schools of Jackfish roam parts of the Tubbataha Reefs and are great attractions for divers and photographers; the Park collects user fees that now cover a large portion of the management costs and compensate traditional fishers for not fishing in the area. (Photo by Alastair Pennycock, 2018)